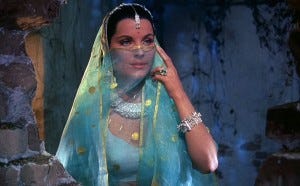

The Indian Epic | Lang

If we’re talking penultimate works, The Beatles have Abbey Road, and Fritz Lang has The Indian Epic. Just like Abbey Road’s victory lap gains an intergalactic resonance through its extended length, synth breakthroughs, and giving Ringo a drum solo, in The Indian Epic Lang returned to German produ…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cinema Year Zero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.