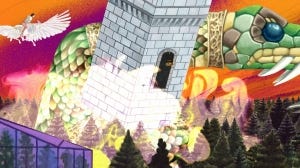

Cryptozoo

Dash Shaw’s animated adult film Cryptozoo (2021) opens as all films should: a naked hippie embalmed in post-coital bliss recounts a dream to his girlfriend. In the dream, visually reconstructed in a fractal kaleidoscope, the 1960s counterculture movement storms the United States Capitol, successfully breaking in and …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cinema Year Zero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.