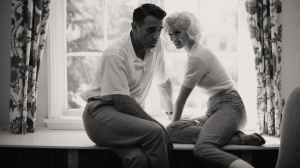

Blonde

If The Buggles had written “Video Killed The Radio Star” today, it may have read more like, “high concept television killed the mid-budget film”. However, mid-budget cinema comprises a large portion of what makes Christmas the cosiest time of the year, because these films are predominantly released during this period. My own…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cinema Year Zero to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.