TROUBLE WITH THE CURVE

“I’m private, I guess, and I’ve found it’s a great pressure to be known.” – Clint Eastwood, Conversations With Clint Eastwood (Kevin Avery)

2012’s Trouble With The Curve opens on a then-83 year-old Clint Eastwood in dialogue with his penis, attempting to coax pee out by berating it with gruff, raspy words. Following a pleasurable piss, he clumsily ambles into a coffee table in the middle of his room, and proceeds to kick it across his house while calling it “bitch”. Cut to: inside the refrigerator as he opens the door and grabs an open can of Spam, utilizing a fork to eat it straight out of the container. Eastwood has been making films addressing his status as an aging cinema icon since Unforgiven (1992) – what critic Amy Taubin called “the first film of Clint Eastwood’s old age”. Clint was not in the director’s chair for Curve, but all films with Eastwood are about “Clint Eastwood”. His is a career spent trying to find unflattering angles of one of American film’s most famous purveyors of violence and taciturn masculinity. In contrast to icons like Chaplin whose late period of melancholic solipsism and leftist politics left audiences befuddled, Eastwood has only grown more prolific and more successful as he has aged, directing 23 films with 4 Best Picture nominations since Unforgiven won in 1993.

“Late Style” is something that this very publication has discussed, and it is worth quoting that piece here to explain why it is a phrase that has seeped into contemporary film discourse in a more pervasive way than ever before:

“Its prevalence as a turn of phrase is no great breakthrough, but a symptom of a film culture that venerates the old, while the Young Turks suffer and fail.”

The term “Late Style” comes from Adorno, a vague, mediated phrase in between the German words Spästil (late style) and Alterstil (individual old-age style), and its use varies; Adorno used it in his essay fragments discussing the third period of Beethoven, where, in his words: the late work “breaks their bonds, not in order to express itself, but in order, expressionless, to cast off the appearance of art”. Current American film is filled with elder statesmen well into their own late periods: Scorsese, Schrader, and Coppola, now all over the age of 80, are still making films. European giants such as Manoel de Oliveira worked until his death at 105. Jean-Luc Godard continues to posthumously innovate after his death at 92. Resnais and Rohmer were still making films in their late 80’s. All of these directors figure prominently in the discourse of what exactly is cinematic Late Style.

Eastwood is an entirely different proposition. A healthy distance from the New Hollywood brats, and certainly not working in the European traditions, he was, and still is, a consummately popular filmmaker. He’s audience-conscious to a fault, Kevin Avery’s Conversations With Clint Eastwood (2011) reveal a man who definitely keeps receipts on box office numbers and critical reviews alike, with the famous example of Pauline Kael’s continual negative scribes causing Clint to get a psychoanalyst to look at her review of The Enforcer (1978) in order to figure out exactly what her problem was (the analyst concluded she was attracted to him). In that same book, Avery puts a question to Eastwood about Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda being unable to find serious work due to their age, with Eastwood conceding that when an actor is a certain age “I don’t think you can base the protagonist of a film on him because there’s no identification factor there.” This was in the early 80’s and now reads like bullshit given his career since then, but proves that Eastwood was wary of the danger involved in aging out of what people know him to be, and his resulting adjustments have become his late style.

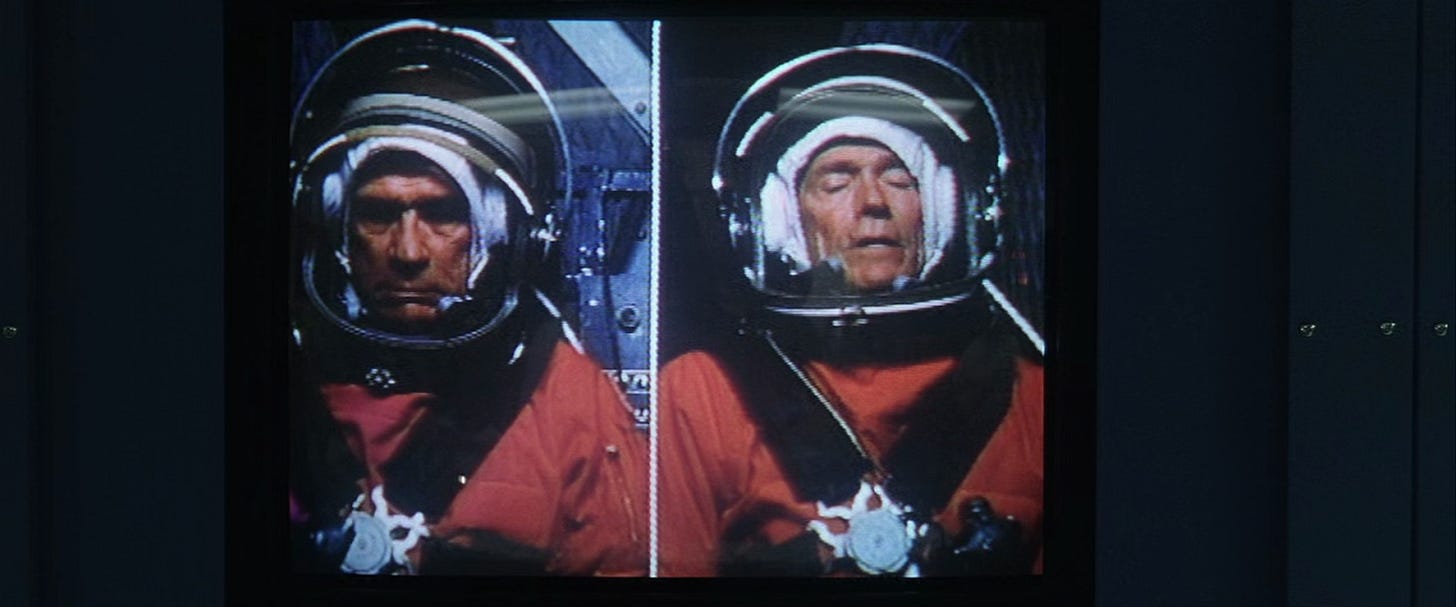

The issue with a catch-all theory of Late Style is that no matter if you die at age 60 or at 105, your last works are your late style. What constitutes late for Eastwood? Is it when he draws attention to his age by getting stuck with a younger sidekick in the buddy cop flick The Rookie (1990)? What about even earlier, where the man made famous through on-screen violence drinks himself to his first film death in Honkytonk Man (1982)? Both feel inadequate, but if we take Taubin at her word, is it fair for a ‘late period’ to be over 30 years? Edward Said says Late Style “has the power to render disenchantment and pleasure without resolving the contradictions between them” and that this tension “is the artist’s mature subjectivity, stripped of hubris and pomposity, unashamed either of its fallibility or of the modest assurance it has gained from age and exile”. Replace “the artist” with “Clint Eastwood” and that reads as if it is a synopsis of Unforgiven. But does it adequately explain Space Cowboys (2000), or The Mule (2018)?

In Trouble With The Curve, Justin Timberlake plays amateur scout Johnny Flanagan, who previously had a hotshot baseball career of his own. Known for his 100mph fastball, he was scouted by Gus (Eastwood) back in the day, but against Gus’s advice, he kept chasing velocity and injured his arm, ending his career. Current day Major League Baseball is facing an epidemic of younger pitchers blowing out their elbows even before they get their beaks wet in the league, with this problem largely attributed, as in Trouble With The Curve, to a league-wide chase after the arms who can throw the hardest in spite of the clear injury risk involved. This epidemic has had me thinking a lot about Jamie Moyer. The left-handed pitcher from Sellersville, Pennsylvania began his professional career in the middle of the Reagan administration and threw his final pitch just as Barack Obama was wrapping up his first term, coincidentally the same year Trouble With The Curve was released.

Moyer was a late bloomer, an early career plagued by inconsistency until elbow surgery in the early 90’s caused him to rethink his whole approach and find his ethos: say no to velocity. His fastball that previously hit the high 80s during his early days now sat between 80-84mph, a good 10mph below the league average that only went up during the course of his career. This move prolonged his professional life in a way the MLB hasn’t seen since. At age 39, when most athletes are considering retirement, he became the best pitcher on the record-setting 2001 Seattle Mariners. A signature languid, disguised delivery aided what would normally be called a late career renaissance, but he was never as good as he was from age 35 onwards, even winning a World Series as a key member of the 2008 Philadelphia Phillies. At the time he retired at the age of 49, he had faced almost 10% of all MLB hitters in the League’s history. Is what Jamie Moyer did Late Style? Here’s Hall of Fame Third Baseman Chipper Jones on the subject, after Moyer shutout his Braves in 2010: “The guy is eighty-seven years old and is still pitching for a reason. He stays off the barrel of the bat. He changes speeds, changes the game plan, keeps you guessing.”

We now have three definitions courtesy of Adorno, Said, and Chipper Jones. Adorno focuses on breaking the bonds of one’s art, but in looking at films like True Crime (1999) or Mystic River (2003), I think one would be hard pressed to make the argument that Eastwood has broken any bonds involved in his art. Said says in aging, an artist becomes less ashamed, and their “mature subjectivity” becomes less interested in resolving the contradictions inherent to one’s youth. While aspects of this map well onto Unforgiven, Eastwood’s screen presence in old age is defined by an all-encompassing shame. Eastwood’s late characters are in some sense failures, where the wrinkles on his face and elderly gait of his walk give the sense that they are load-bearing for wrongs committed in past lives. Million Dollar Baby (2004) may look like a traditional weepie, but it savagely depicts Eastwood desperately taking advantage of a lower-class woman’s athletic talents to try and relive past successes that we aren’t sure ever existed. Gran Torino (2008) is another of the rare Eastwood films where he dies in the end, where the sun is barely seen until he has passed away, and where Eastwood has his fortune read by a Hmong Shaman, who says to the lonely old man “you have no happiness in your life.” With Gran Torino, Clint actually set the record for the oldest leading man to reach #1 at the box office.

The Chipper Jones definition has a simple wisdom in tune with how Eastwood discusses his work. The answer to longevity is, like Jamie Moyer, to misdirect and say no to velocity, where old age doesn’t provoke these trite maxims about a found inner peace, but instead complicates long-held ideas and sacred iconographies, biting around the edges of one’s own persona. Eastwood’s presence on screen or name above the title has a unique effect of obscuring just how strange his films, especially in the 21st century, really are. Of course he’s interested in masculine, reticent, American dignity, but as he has aged he’s found it in increasingly strange places. There’s an airline pilot, capable of saving the lives of hundreds but unprepared to navigate the subsequent Langian media trap in Sully (2016), or a cop-loving Paul Blart figure forced to become Antigone in Richard Jewell (2019), or remaking Close-Up (1990) with three army washouts re-enacting their own European vacation, selfie-sticks and all, only to later violently re-create their own heroic act, in The 15:17 To Paris (2017). He turns a biopic of a conservative American hero in J. Edgar (2011) into a gay melodrama worthy of Fassbinder, the streets of South Boston into Dostoevky’s Saint Petersburg for Mystic River (2003), and an airport-paperback style plot into a meditation on the metaphysics of loneliness with Hereafter (2010). Even when he is not acting, he is an artist whose choices are always more off-kilter than he is ever given credit for, a dexterous ability to “stay off the barrel of the bat” and maintain the high-wire act involved with being immensely famous and inexorably strange, even alienating.

The aspect of Eastwood’s late style most in line with Said and Adorno is the proximity to death, which by all available evidence, will be the only thing stopping Eastwood from continuing to make films (Trouble With The Curve again: “He wouldn’t do well without his work”). Death is foundational to Eastwood’s late filmography: the murders in Mystic River, the assisted suicide in Million Dollar Baby, or war casualties ricocheting onto the home front in American Sniper (2014). There are no happy families in an Eastwood film, always signifying a kind of spiritual death, so many of his characters have dead wives and estranged children. Forever a cowboy in old age, since The Man With No Name to be Clint Eastwood is to stand apart from society, what has changed from Unforgiven onwards is the nagging sense that life just won’t leave him alone.

The apotheosis of Unforgiven’s “one last job” ethos is 2021’s Cry Macho, a late style urtext if there ever was one. Eastwood plays Mike Milo, a widowed, alcoholic former rodeo rider who is inexplicably hired by his former employer to track down his estranged son (Eduardo Minett) in Mexico City. From Absolute Power (1997), to Space Cowboys, to The Mule, Eastwood has gotten a lot of mileage out of placing himself within plots that would better fit a younger version of him. Narrative traps are evaded comically easily: a police roadblock conveniently has a dirt road right before it; Minett and Eastwood coincidentally stop right outside of a clothing store when they need a quick change; their car breaks down but Minett found another that even has the keys in it, etc etc. Plot matters little, the film exists to watch Eastwood amble through its world, exchange simple wisdom about masculinity with Minett, ride horses, heal animals, and relax by the setting sun.

We are firmly in the Seven Woman (1966)/Rio Lobo (1970) late style territory of Ford and Hawks, beautifully artificial obstacles in service of works that feel unfinished, out of touch with a viewing public, and repetitive in the context of one’s career. If The Mule, like a late Rembrandt, is suffused with doubt about the self in spite of its “smell the flowers” ending in prison, Cry Macho casts off that doubt with an ending that functions as a feint. Clint completes the job and rides away, but instead of riding into exile Searchers-style, he reprises an earlier scene. The finale has him once again slow-dancing with the Mexican restaurateur whom he formed an attachment with in the film, a sunlit haze cloaking the proceedings, almost like a dream. Practically, it makes no sense. Mike Milo doesn’t speak Spanish, and there is a near 40 year age gap between Eastwood and the actor Natalia Traven, but if these are things that bother you, you probably turned the movie off a long time ago. The Moyer-style changing of speeds here is simply the fact that it is possible for an Eastwood character to find exile and Eden in the same place, although it has taken him a whole career’s worth of crooked roads to feel like he has earned it.

Something funny about the various convergences between film and sport is that a lot of critical discussion about a director’s body of work often reads in a similar manner to a commentator discussing an athlete’s career. Think of times people refer to filmographies as if they formed a neat arc. Inevitably there’s a “youthful” and “energetic” debut that progresses into the “prime” of a director’s career with a string of major works, leading to a tailing off in the quality of the films but always “mature” and “assured” works nevertheless. One thinks of what Nicholas Ray once said to Buñuel, who listened in horror as Ray told him that in order to be a success in Hollywood, your next film must have a bigger budget than the previous one, otherwise you start sliding backwards, industry-wise.

Director’s careers never form as neat of an arc as we’d like to impose on them, and much of the discourse surrounding late style is a simple fetishization of an accumulated elderly wisdom rather than Actually Looking at what’s on screen. As Sinatra got older, he used to end his performances by crooning: “And may the last voice you hear be mine…” Pretty corny, but he knows he’s speaking to an audience that made him into a symbol of a time period, and emblematic of certain feelings his voice evokes. Whether it is using Sinatra’s Fly Me To The Moon at the end of Space Cowboys, or Trouble With The Curve’s triumph over the evils of statistical analytics, or Cry Macho reusing a scene to imagine paradise, Eastwood has gotten cornier as he has aged, but this exists alongside the subversions of his persona, the weirdness of his script choices, and a whole popular body of work we are unlikely to see ever again in American cinema. At this point, Eastwood, like Jamie Moyer every time he pitched, is an anachronism. He has made and remade himself on screen for decades, but he is not the isolated composer of Beethoven’s Third Period that Adorno describes, or the literally exiled Chaplin of A King In New York (1957). In spite of the fates of his characters, or the strangeness of his films, Eastwood remains a recognized figure who knows exactly who he is talking to. For truly late style, ya gotta earn it.

Cinema Year Zero is volunteer run. Our goal is to pay writers a fair fee for their work. So if you like what you find at Cinema Year Zero, please consider subscribing to our Patreon!